Heat stress is an invisible killer. It’s time to act now!

“There is an urgent need for new, evidence-based and comprehensive measures to protect the health and lives of all workers, in all sectors, and in all regions of the world, with the overall goal of advancing social justice and promoting decent work for all.”

ILO Report, “Heat at work: Implications for safety and health

Summary of the ILO Report “Heat at work: Implications for safety and health”

The ILO report “Heat at work: Implications for safety and health” paints a stark picture of a rapidly warming world, where 2023 was the hottest year on record, followed by consecutive months in 2024 that broke previous temperature records.

This trend has serious implications for the safety and health of workers around the world. Many workers are especially vulnerable to extreme temperatures, but have no choice but to continue working in these dangerous conditions. The report highlights how heat stress, an invisible but deadly threat, can lead to immediate health problems such as heat exhaustion, heat stroke and even death. In the long term, chronic diseases of the cardiovascular, respiratory and renal systems, as well as mental health problems and increased workplace accidents and injuries, are becoming more common among workers exposed to excessive heat.

The report also focuses on the way forward and concrete solutions. La Isla Network is proud that one of our initiatives, the Adelante Initiative, is referred to in the report of the International Labor Organization as a case study of SUCCESS in the fight against occupational heat stress. Please continue reading to learn more about how our work is already addressing the needs set by the ILO, and the Adelante Initiative.

Table of Contents

F.A.Q

How many workers are exposed to excessive heat yearly?

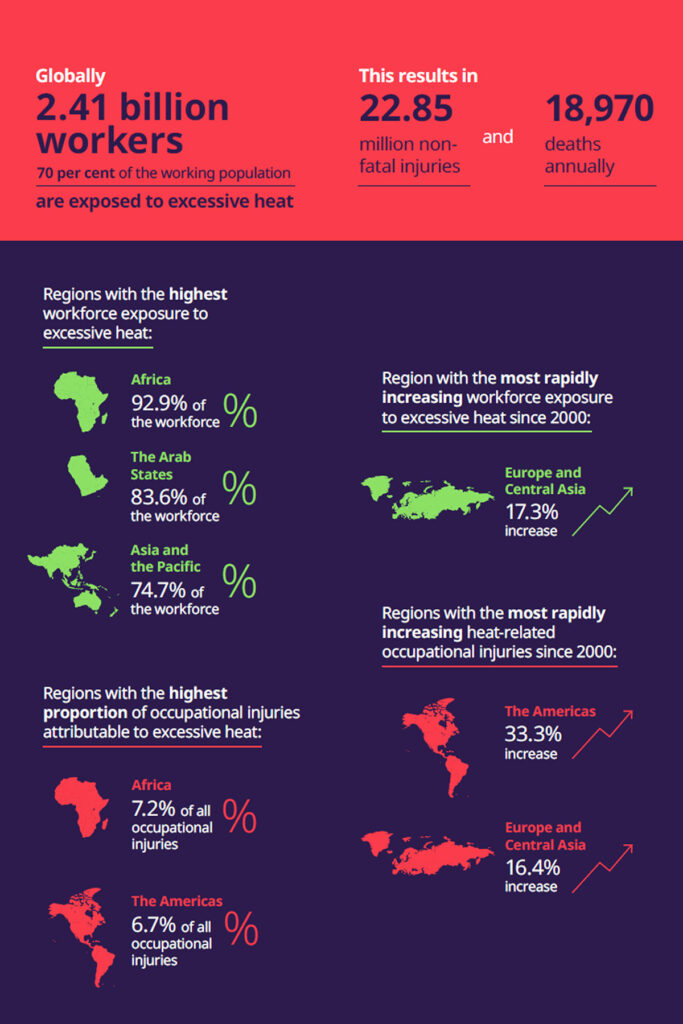

- Worldwide, 2.41 billion workers are exposed to excessive heat, or 71 percent of the global working population.

- In three major regions workplace exposures to excessive heat exceeded the global average: 92.9% in Africa; 83.6% in the Arab States; and 74.7% in Asia and the Pacific.

How many more workers are exposed to excessive heat since 2000?

- 8.8% more workers are exposed to excessive heat from 2000 to 2020.

- Europe/Central Asia witnessed the highest increase. 17.3% more of its workers are now exposed to excessive heat.

How many occupational injuries and deaths are attributable to excessive heat?

- Every year excessive heat results in 22.85 million injuries and 18,970 deaths on the job.

- Africa and the Americas are the regions with the greatest share of documented occupational injuries attributable to excessive heat: 7.2% and 6.7% yearly.

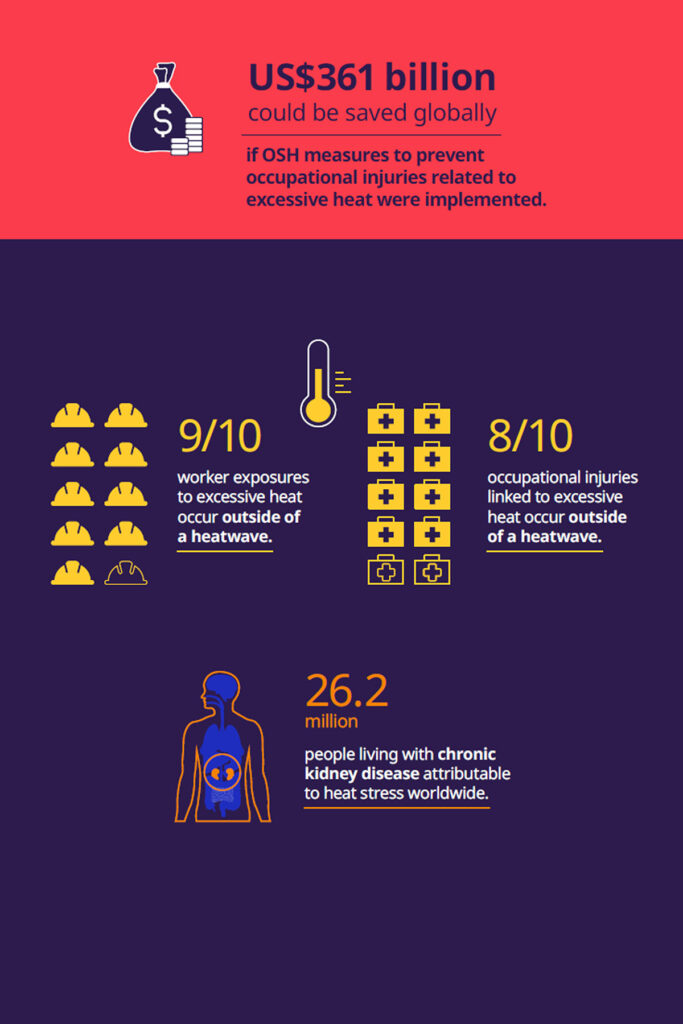

- In 2020, there were 26.2 million people living with chronic kidney disease attributable to heat stress in the workplace worldwide, constituting approximately 3% of all chronic kidney disease cases.

How has the frequency of occupational injuries from excessive heat changed since 2000?

- Occupational injuries from excessive heat continue to increase.

- Since 2000, the largest increase of injuries has been witnessed in the Americas and Europe/Central Asia: 33.3% and 16.4%.

When are worker injuries most likely to occur?

- Nine out of ten worker exposures to excessive heat occur outside of a heatwave.

- Eight out of ten heat-related injuries occur outside of a heatwave.

What can OSH measures do to prevent worker injury and financial loss?

- Implementing OSH measures to combat excessive heat exposure would save up to 361 billion USD was described in the ILO report.

- La Isla Network OSH interventions implemented in the Adelante Center of Excellence have achieved the following: reduced hospitalizations related to occupational heat stress by 80%, increased the productivity of workers by 10% to 20%, and provided a return on investment of 22% for the mill. Learn more about the Adelante Initiative in the ILO Report.

Key Lessons Learned from the ILO report

- Simple and Affordable Practices: Effective workplace protections are often low-cost and easy to implement, such as hydration, rest areas, sanitation, adjusted work schedules, and acclimatization programs.

- Strengthen Heat Stress Prevention: Urgent improvements are needed for heat stress prevention and control, as current strategies are inadequate against rising temperatures (i.e. rest, breaks or modified work schedules to limit or avoid exposure to excessive heat, including the ability to self-pace).

- Integrate OSH in Heat Action Plans: Worker protections should be central to heat action plans and public health campaigns, treating heat as an OSH hazard.

- Continuous Protection During Excessive Heat: Protective measures must be in place during all periods of excessive heat, not just heatwaves, with a rights-based approach ensuring safe working environments.

- Tailored Strategies for Sectors: Develop specific strategies for different sectors and environments, including both indoor and outdoor workers, especially in vulnerable settings.

- Integrate Heat Stress in OSH Systems: Heat stress prevention should be a part of OSH management systems, incorporating workplace risk assessments and worker input.

- Foundation of Social Dialogue: Social dialogue is essential for developing and implementing heat stress policies, with empowered worker participation and collective bargaining agreements.

- Collaboration Across Sectors: International, inter-governmental, and cross-sector collaboration is crucial for sharing knowledge and resources to address workplace heat stress.

- Need for Research and Knowledge Exchange: Targeted research and global knowledge exchanges are needed to assess interventions’ effectiveness and harmonize heat stress assessment and intervention models.

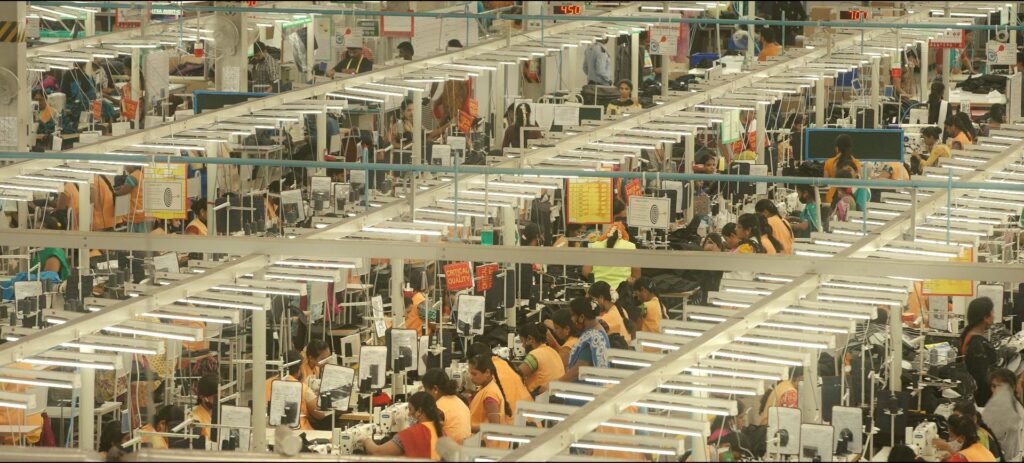

Photo credit: © M. Crozet / ILO

What the ILO highlights about occupational heat stress and its global burden

- The ILO recognizes that excessive heat poses a significant threat to worker safety, health, and well-being for indoor and outdoor workers — and urges taking preventive measures now. To bolster the urgency of the issue, UN Secretary General António Guterres has issued a call to action on extreme heat.

- Excessive heat can immediately impact workers on the job by leading to illnesses such as heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and even death. In the longer term, workers are developing serious and debilitating chronic diseases, impacting the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, as well as the kidneys or mental health. The examples provided include mild and serious effects such as heatstroke, fluid/electrolyte disorders, cardiovascular impacts/disease, respiratory impacts/diseases, acute/chronic kidney injury, mental health effects, and accidents and injuries.

- The ILO highlights CKDnt and argues that its etiology is currently unknown. However, it mentions its relationship with heat stress in the workplace as the main hypothesis, although it also mentions other lines of evidence involving environmental, genetic, or socioeconomic exposure factors that exacerbate the effects of heat stress.

- The ILO recognizes that workers are among those most exposed to extreme temperatures.

- Heat-related health risks disproportionately impact workers in precarious situations who have a lower capacity to adapt. This makes them more susceptible to heat-related illnesses, yet they frequently have no choice but to continue working despite the huge risks. However, these illnesses can arise even in individuals deemed low-risk (such as young, fit adults with no history of heat-related illnesses) who follow effective heat prevention strategies.

- New, evidence-based, and comprehensive measures to protect workers’ health and lives are urgently needed. The overall goal is to advance social justice and promote decent work for all.

- Workers should be at the heart of heat action plans, early warning systems, and other heat-related public health efforts. Excessive heat and heatwaves should be treated as OSH hazards.

- The analysis of various national legislations addressing heat stress reveals that few countries recognize excessive heat-related diseases as occupational diseases, in accordance with the ILO List of Occupational Diseases.

- Many of those countries use the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) as an indicator to assess heat exposure levels.

- The thresholds adopted in the legislations analyzed are typically 29-30°C for high-intensity work, 30-31°C for moderate-intensity work, and 31.5-32.5°C for low-intensity work.

- Strategies to prevent heat stress include varying safety thresholds depending on work intensity, strategies for hydration, rest, shade, ventilation, acclimatization, use of PPE, awareness of heat stress and heat-related illnesses, periodic medical check-ups, and health monitoring, among others.

- The ILO cites examples of the impact of legislation to mitigate heat stress, such as the case of Qatar, where hospitalizations related to heat stress in the workplace were reduced by more than half after new legislation was adopted.

- Despite the presence of laws and regulations aimed at safeguarding workers from heat stress, many of these provisions were established in the past, often using requirements that fail to address the complexities of contemporary understanding of heat stress challenges. Even today, as the impacts of climate change intensify and grow, countries must often develop policies and legislation quickly, in order to address rapidly evolving risks.

- The ILO recognizes that workers need a rights-based approach outlined in Convention No. 155.

- This convention includes workers’ fundamental right to a safe and healthy working environment, the right to know about heat stress, and the right to remove themselves from dangerous situations. Employers are responsible for conducting thorough risk assessments to identify situations where workers may be exposed to excessive heat, in line with this convention.

- The ILO has outlined 10 characteristics to guide the development of effective workplace action plans, most of which align with the LIN methodology.

- Participatory risk assessment in the working environment integrating excessive heat.

- Identification of and targeted strategies for worker groups at high risk.

- Use of the WBGT as a potential heat stress indicator to assess the level of heat exposure, with varying safety thresholds based on work intensity. La Isla Network favors the WBGT over dry bulb temperature and the heat index because WBGT includes other factors such as UV exposure.

- Hydration strategies, including adequate sanitation facilities, especially for female workers.

- Rest, breaks or modified work schedules to limit or avoid exposure to excessive heat, including the ability to self-pace and the ability to take breaks when workers determine it is necessary.

- Provision of cool, shaded and ventilated rest areas.

- Heat acclimatization programs for workers without recent heat exposure.

- PPE designed to protect workers from heat stress.

- Education and awareness on heat stress and heat-related illnesses.

- Regular medical check-ups and health monitoring.

- ILO describes in detail five key concepts of an OSH management system intended to protect workers from heat-related illnesses and injuries in the workplace:

- Workplace-level risk assessment, including identifying hazards, evaluating risk, monitoring and reviewing the risk assessment, and updating it when necessary in a way that includes workers.

- Heat stress prevention and control practices include cooling the work environment, reducing workers’ exposure to excessive heat (ensuring adequate hydration, introducing work-rest cycles, acclimatization, and implementing job/task monitoring programs), and providing PPE.

- Education and awareness on heat stress. ILO states that effective training on the risks of excessive heat should be carried out regularly, particularly before the onset of warmer seasons, to raise awareness of the signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses, including an acclimatization program.

- Monitoring worker health for heat-related illnesses or accidents. Individuals should be assessed for their ability to cope with heat stress before they start a job and periodically thereafter, thorough physical examination with relevant tests (ILO proposes a table with response guidelines to identify heat-related illnesses and to understand the appropriate emergency first aid and other necessary actions).

- Role of workplaces in the mitigation of climate change impacts, ILO notes that enterprises should adopt technologies and practices that also contribute to lowering greenhouse gas emissions in the framework of a just transition.

Workplace Actions on Heat Stress

What has ILO recognized as the importance of the Adelante initiative and the PREP methodology in recognizing and facing heath stress in workplaces, how is it similar or different from other experiences?

- ILO has highlighted the Adelante Initiative developed by La Isla Network, jointly with Ingenio San Antonio and Bonsucro, as one of six workplace examples of plans to prevent and control heat stress in different regions of the world.

- The report highlights that La Isla Network’s PREP methodology for prevention and protection against heat stress is based on a simple concept that facilitates effective management and logistics in complex contexts. The report acknowledges that the intervention at the San Antonio sugar mill in Nicaragua resulted in a 94% reduction in cases of acute kidney injury due to excessive heat, the elimination of fatal heat stroke cases, a 10-20% increase in productivity, and a positive return on investment of 22% through the reduction of accidents, staff turnover, and absenteeism.

- The other five examples cited by ILO share some of the strategies LIN suggests for heat stress prevention and control, with some variations that may be of interest as learning opportunities, as summarized below:

- Vision Zero Fund in Mexico and Vietnam is working to establish a methodology for measuring heat exposure and heat stress among agricultural workers, identify main hazards, to recommend national regulatory improvements to address occupational heat stress, and to develop workplace-level guidance for employers.

- Their study recommended that pilot studies of adaptive strategies involve workers throughout their design, implementation, and evaluation, and using a community-based participatory research approach to support the uptake of recommendations and facilitate understanding of interventions’ feasibility, effectiveness, sustainability, and scalability.

- Vision Zero Fund in Mexico and Vietnam is working to establish a methodology for measuring heat exposure and heat stress among agricultural workers, identify main hazards, to recommend national regulatory improvements to address occupational heat stress, and to develop workplace-level guidance for employers.

- The ILO’s Better Factories Cambodia program addresses indoor heat in Cambodian apparel and footwear factories. It highlights the critical role of consistent data collection and innovative solutions in creating safer and more sustainable working environments. Integrating wet-bulb temperature readings could provide a more accurate picture of the heat stress faced by workers.

- The HEAT-SHIELD warning platform in Europe developed a heat stress alert system, being the first web-based platform to provide both short-term (weekly) and long-term (monthly) guidance to protect workers’ health and productivity. This enables workers, employers, and other key stakeholders across different industries in Europe to plan and implement the most suitable prevention measures.

- The HeatSafe project in Singapore seeks to understand how our warming climate affects Southeast Asian workers’ health, well-being, and productivity and identify sustainable preventive policies and actions that can reduce these impacts. The intervention consisted of increasing scheduled breaks, improving water supplies, improving work attire, and training supervisors and workers to raise awareness of heat stress and heat-related illnesses through an educational video.

- The Sri Ramachandra Institute workplace heat stress prevention plan in India assessed the workload and heat stress of workers in brick kilns and evaluated kidney function. The results led to a heat stress prevention plan to reduce workers’ exposure to excessive heat and improve their overall health and well-being. The program included providing shaded areas and rest breaks, improving access to toilets, including tools to reduce manual labor, and introducing health insurance schemes to help workers access medical care and resolve health problems. The results of the plan showed a significant reduction in the heat stress and thermoregulatory challenges experienced by workers and recorded significant improvements in their heat-related illness symptoms, including kidney function. For more information please consult the biosketch of lead scientist Vidhya Venugopal.

How are La Isla Network’s ongoing efforts aligned with what the ILO suggests for action on extreme heat?

Strengthen heat stress prevention

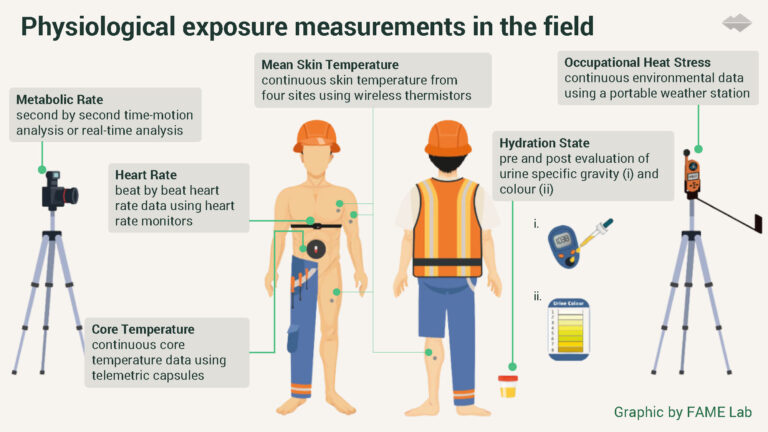

Strengthen heat stress prevention. Our work improves on heat standards by making them specific to the worksite. Unfortunately, many heat standards and rules that govern the workplace are not physiologically relevant to how workers’ bodies respond to the conditions at the worksite. For example, a component of some standards is cutoff temperatures, which limit work at certain temperature thresholds, but they don’t account for the burden of heat from metabolic workload. Though the regulations in standards are based on scientific evidence, they can be further strengthened via data monitoring (Figure 1), opening the path to the elimination of harm to worker health and generation of a positive return for the business.

Integrate OSH in heat action plans

Since our founding we have been steadfast in our commitment to protecting workers in a changing climate. We believe that workers are the so-called “canaries in the coal mine” of climate change. They will be affected first and the hardest by all aspects of climate change, especially extreme heat. Ensuring their health and well-being, while promoting their dignity and right to a safe and healthy working environment, ensures that the world can continue to enjoy the prosperity that they play no small part in creating.

Continuous protection during excessive heat. Heat can affect us without our knowledge, even when we think it’s not “hot”. In fact, even moderate temperatures can pose a risk to workers on the job. The fact that most injuries occur outside of heatwaves shows us that while we are rightly averse to extreme temperatures, avoiding harm from imminent danger, we might make the mistake of thinking that lower temperatures are not also dangerous. Consider the research findings from our project with Turner Construction. On a week where the peak temperature was lower than average (88°F/31.1°C, July 2023, Midwestern U.S.) 43% of workers experienced peak core temperatures exceeding 100.4°F/38°C. Furthermore, 4% of workers’ core temperature exceeded 101.3°F/38.5°C. (For context, hyperthermia begins to threaten life at 104°F/40°C.)

Tailored strategies for sectors. We have shown how our work is specific to the worksite. We have years of experience applying our method to various sectors, commodities and countries. Sectors: Agriculture, Mining, Construction, Textile, Manufacturing and Fabrication. Commodities: Sugarcane, Salt, Rice, Radishes, Lettuce, Cotton. Countries/Regions: United States, European Union, Great Britain, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Spain, Greece, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Barbados, Brazil, Jamaica, Mexico, Costa Rica, Nepal and Malaysia. Our work is having a positive impact in the supply chains of our various partners, including Ingenio San Antonio, Diageo, Coca-Cola, Turner Construction, Sainsbury’s, G’s Fresh, Adidas, Calibre Mining Group and more.

Integrate heat stress in OSH systems. When it comes to the health of business, we understand that the way the management team perceives the relationship between worker health and productivity matters too. We include organizational management assessments as part of our transdisciplinary approach. We conduct all parts of the research with transparency and build evidence on-site, which is translated into policy and practice. Following this model framework we are able to build a Center of Excellence, translating evidence collected on-site into policy and practice that best addresses the OSH risks found at the worksite and following through on effective implementation to ensure long-lasting change.

Simple and affordable practices. La Isla Network offers practical, evidence-based solutions to implement simple and cost-effective measures targeting adequate hydration, shaded rest areas, and modified work schedules. Our expertise ensures that these interventions are tailored to the specific conditions of each worksite, maximizing their effectiveness and affordability.

Foundation of social dialogue. We facilitate social dialogue by training and empowering workers and their representatives to actively participate with management in the development and implementation of heat stress policies. Through collaborative engagement, La Isla Network helps foster effective dialogue that address specific workplace conditions, fostering a culture of open communication and shared responsibility.

Collaboration across sectors. La Isla Network promotes international, inter-governmental, and cross-sector collaboration by leveraging our extensive network of partners, including governments, NGOs, private companies and multilateral institutions. We work to harmonize policies and practices across sectors, ensuring comprehensive and coherent strategies to mitigate workplace heat stress.

Need for research and knowledge. This is our bread and butter. We lead targeted empirical research and global knowledge exchanges to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and develop harmonized heat stress assessment and intervention protocols. By sharing our findings and best practices, La Isla Network contributes to a robust science-policy interface, enhancing global understanding and response to heat stress challenges in the workplace.