Crossing New Borders—Investigating CKDnT in Texas

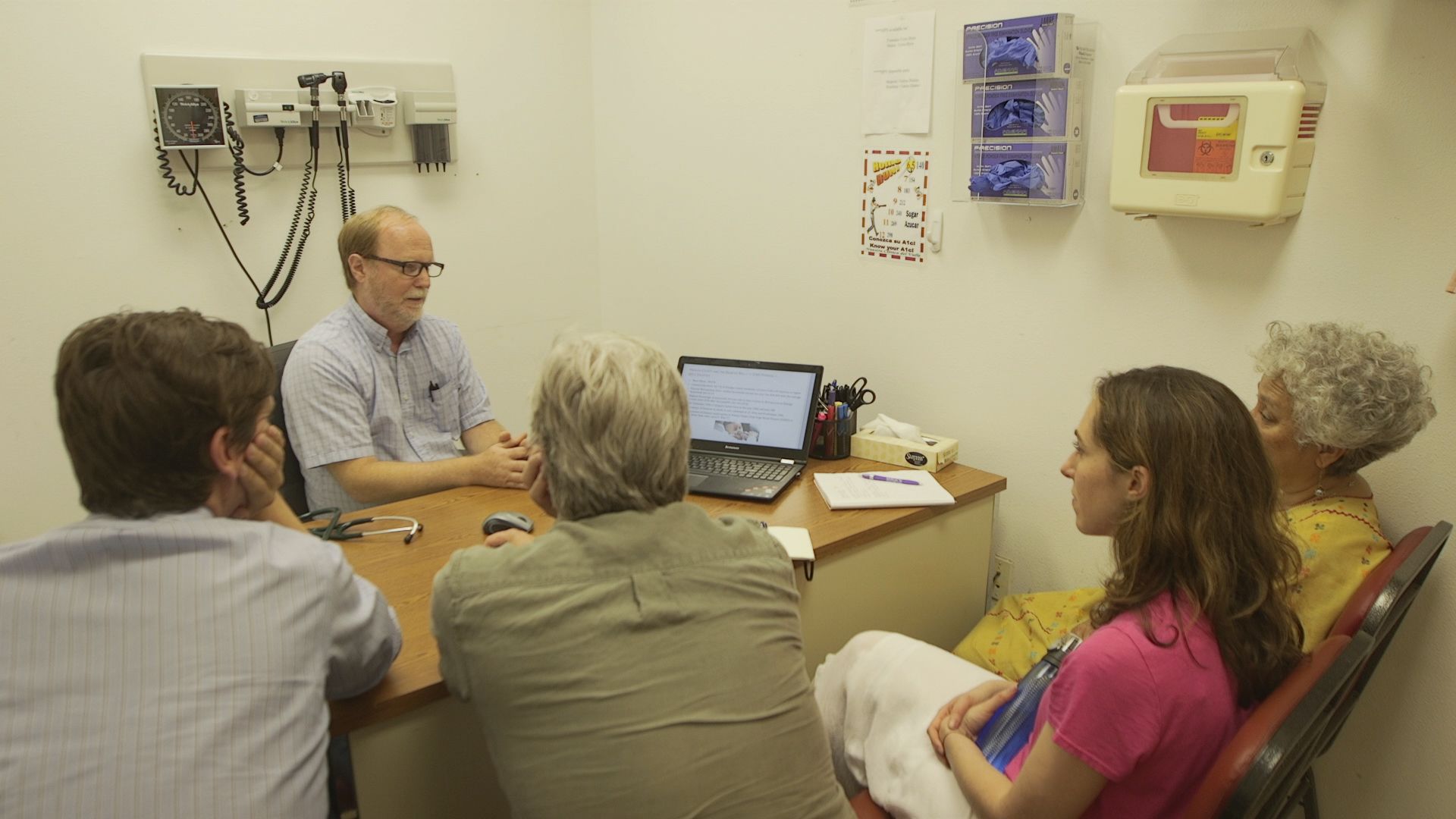

Video screenshots of LaIsla Network and Migrants Clinician Network investigating Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown origin in South Texas. Members of La Isla Network meet with the Mexican consulate in McAllen, Texas. July 2017

The temperature read 95 degrees Fahrenheit at 8:29 pm as we rolled through Del Rio, Texas. A small group of La Isla Network members and partners had spent the last few days in Austin, meeting with researchers and clinicians about the presence of CKDnT. Now we were on our way towards the Mexican border. It’s an anxiety ridden time for many in Southern Texas, with political will centered on anti-immigration and the deportation of undocumented workers. We were traveling into unfamiliar territory, even though we were in our own country. Our partner Del Garcia, with Migrant Clinicians Network, guided us through this hazy landscape as we took meetings with clinicians, local activists and members of several Mexican consulates. The stories we heard were bleak: border patrol agents cruising consulate parking lots looking to arrest “illegals,” people with CKD on dialysis in ICE detention centers waiting to be deported, and the uncertainty of care for patients returning to Mexico.

One of the main issues with CKDnT is that it almost exclusively affects people of very vulnerable populations, namely agricultural workers in Central America and South Asia, and as evidence points to, many other parts of the world. What is unique about Texas, is the added vulnerability of being undocumented that many young men face. This means that people who are already at high risk of developing CKDnT due to strenuous working conditions in agriculture or construction, may not seek healthcare for fear of being registered in the system. Once registered, they may be reported and deported without receiving treatment. For many, just the possibility of losing their job is enough to discourage seeking care. One agent from OSHA who met with us and wished to remain anonymous claims that 24 men have died in the San Antonio district in the past 8 months, mainly due to safety failures in construction and lack of training, which men forgo to not miss work, or because their bosses don’t allow them to miss work for training. While the deaths are reported, the OSHA violations are not, largely due to the national administration change. This paints a picture of a construction industry not protecting its workers and a system incapable, or unwilling to penalize occupational health and safety violations.

Possibly obscuring the rate of CKDnT among this population is the overwhelming presence of another epidemic of CKD; that due to diabetes. Dr. Brian Wickwire, who runs a federally funded clinic in Rio Grande City along the US-Mexican border is overwhelmed by how many of his patients suffer from diabetes. In fact, 50% of the population in Rio Grande City are diabetic or pre-diabetic. He mentioned that among some patients, especially the young men, he was surprised by how quickly people were going from diagnosis to end stage kidney disease. This extremely fast rate of deterioration of kidney function is not a typical pattern for CKD patients and raises questions about whether they may be suffering from CKD and CKDnT simultaneously—something further to investigate.

Oscar Benavides, a former migrant worker who now works with the healthcare system in Austin, assists patients who need to return to Mexico either forcibly for legal reasons, or by choice. He claims that he has 12 patients currently who have CKDnT, the majority of them young, former manual laborers. After speaking with a number of primary care physicians, it is clear that there are cases of CKDnT, mainly in the immigrant and migrant workforce. The question that remains is: are people getting sick working in the US, or are they arriving from countries like Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador with early stage CKDnT? For now, it’s too early to tell, however, the connections made on this short investigative trip set the framework for future research relationships. LIN hopes to begin assessing prevalence working with the Mexican consulates and clinicians and is aiming to launch a DEGREE protocol with local researchers to identify if there is a problem, where it is, and who is affected.

Looking over the border towards Mexico, after all the time spent in Latin America working to prevent CKDnT, we find ourselves on American soil, where for many, the conditions are the same, and in some cases, worse.

Tom Laffay

Tom Laffay is an American photojournalist and filmmaker dedicated to issues of human rights, public health and conflict.