When Addressing Exertional Heat Stroke, Think:

Act with HASTE

H.

Heat exposure: Identify if the individual has been in a hot environment or engaged in rigorous activity.

A.

Altered mental status: Look for signs like headache, confusion, combativeness, fainting, ataxia, or disorientation.

S.

Start cooling: Begin cooling the patient immediately with cold or ice water. If there's no pulse, start CPR.

T.

Time: Recognize the urgency. If these signs are present, call 9-1-1 immediately.

E.

Emergency: Act quickly to prevent further complications and ensure the best possible outcome.

The Importance of

H.A.S.T.E.

in Addressing Exertional Heat Stroke

As the world faces what could be the hottest summer on record in 2024, understanding and addressing exertional heat stroke (EHS) is more critical than ever. EHS is a life-threatening condition that can occur rapidly in healthy individuals engaged in intense physical activities in hot environments. This distinction sets it apart from classical heat stroke (CHS), which typically affects the ill, elderly, or those with comorbidities during heat waves. The need for improved public health messaging on EHS is vital, as evidenced by recent findings and recommendations from experts in the field.

Worker Accused of Being on Drugs Was Experiencing Heat Stress

Occupational heat stress can lead to exertional heat stroke. Before heat stress gives way to physical collapse, a worker might experience altered, erratic behavior.

This was the case for Gabriel Infante, a 24-year-old construction worker who had been laying fiber optic cables in San Antonio, Texas when he succumbed to the heat from the Texas sun. On June 23, 2022, only a few days into the job, Infante died from a heat stroke, the medical examiner concluded. Because the heat stroke was induced by intense physical activity in the heat, what killed Infante was exertional heat stroke.

Infante and his brother had started working their new jobs at the same time. The work ran from 7 in the morning to 6 in the afternoon. It is unclear what their break schedule was.

On the third day, Infante reportedly had trouble with the heat. The foreman told Infante to sit in the company truck, where the air conditioner was running. He sat there for two hours and no other problems were reported.

But on the following day, Infante continued to have trouble. After lunch, Infante’s coworkers noticed him wobbling on his feet. He said he was fine, but had clearly begun succumbing to heat stress. Later in the day, Infante’s unsteadiness continued. He tripped and hit his head, leaving marks. When his coworkers attempted to pick him up, Infante tried to fight them, indicating his altered mental state. At this point his coworkers called 9-1-1.

Friend and co-worker Joshua Espinoza poured cold water over him, trying to lower his body temperature. A foreman insisted Espinoza call the police, claiming Infante’s erratic behavior was due to drugs. When emergency medical services arrived, the foreman pushed for a drug test.

Tests done at the ER pointed to Infante’s poor condition, including abnormal levels of hemoglobin and white blood cells. There were no toxins or drugs in his body. His temperature was 109 degrees Fahrenheit. He arrived at the hospital unconscious, and died in the ICU the following day.

Following the incident, Infante’s family has filed a lawsuit against his employer, B Comm Constructors.

Understanding Exertional Heat Stroke

EHS can happen suddenly and is often influenced by motivational factors such as athletic competition, work deadlines, or military training. Unlike CHS, which develops gradually, EHS can strike quickly, putting athletes, agricultural and construction workers, and military personnel at high risk. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), excessive heat exposure at work results in nearly 19,000 fatalities annually and over 2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has documented several tragic cases of EHS, highlighting the need for immediate and effective interventions.

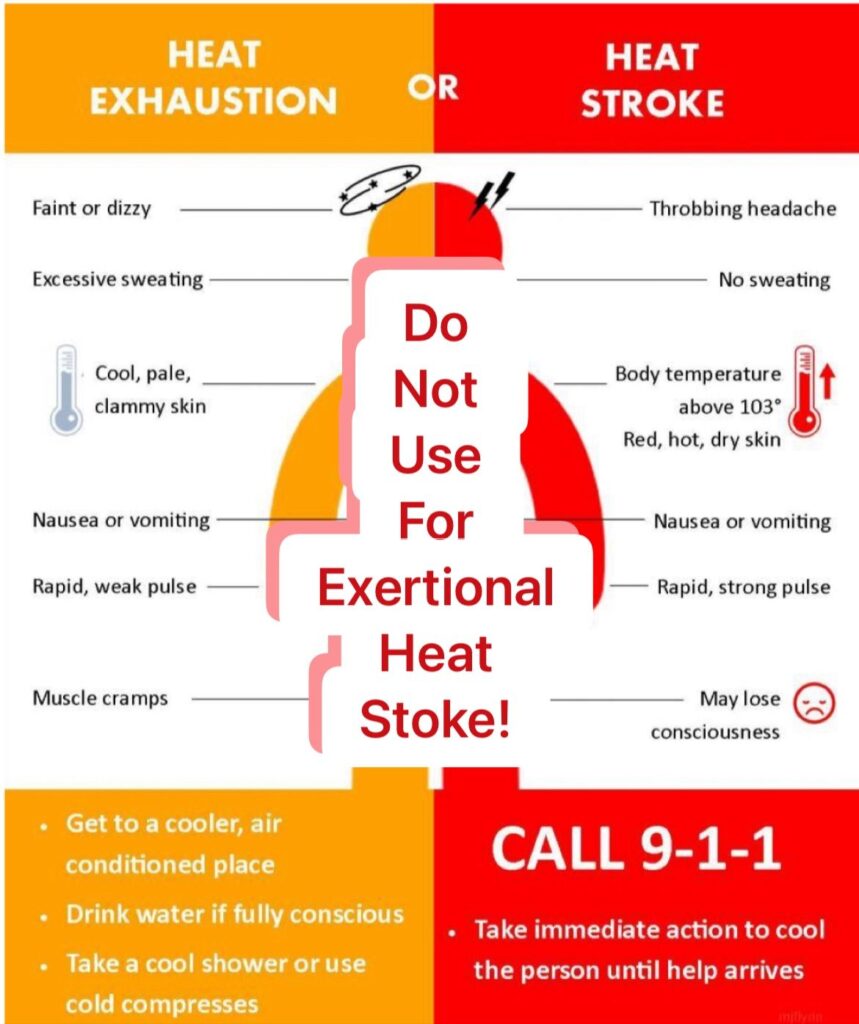

Challenges in Current Messaging

Despite existing guidelines and protocols for EHS, public and first responder messaging often contain conflicting or misleading information. One major issue is the portrayal of "no sweating" as a key symptom of heat stroke. While this may apply to some CHS cases, EHS patients can still sweat profusely. Additionally, the differentiation between fainting (heat exhaustion) and loss of consciousness (heat stroke) can be challenging, even for medical professionals, further complicating the response.

Introducing H.A.S.T.E.

To address these challenges, experts from the Department of Defense, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and American College of Sports Medicine emphasize that changes in mental status—such as confusion, agitation, headache, or loss of consciousness—are critical indicators of EHS. Rapid cooling is the most effective management strategy, and immediate action can be lifesaving.

To simplify public awareness and response, the H.A.S.T.E. acronym has been proposed:

H.

Heat exposure: Identify if the individual has been in a hot environment or engaged in rigorous activity.

A.

Altered mental status: Look for signs like headache, confusion, combativeness, fainting, ataxia, or disorientation.

S.

Start cooling: Begin cooling the patient immediately with cold or ice water. If there's no pulse, start CPR.

T.

Time: Recognize the urgency. If these signs are present, call 9-1-1 immediately.

E.

Emergency: Act quickly to prevent further complications and ensure the best possible outcome.

H.

Heat exposure: Identify if the individual has been in a hot environment or engaged in rigorous activity.

A.

Altered mental status: Look for signs like headache, confusion, combativeness, fainting, ataxia, or disorientation.

S.

Start cooling: Begin cooling the patient immediately with cold or ice water. If there's no pulse, start CPR.

T.

Time: Recognize the urgency. If these signs are present, call 9-1-1 immediately.

E.

Emergency: Act quickly to prevent further complications and ensure the best possible outcome.